Finding the Path.

A key piece of implementing UNDRIP is having sessions just like this.

— Chief Willie Sellars, Williams Lake Indian Band

Final report.

A historic gathering in early 2020 brought together nearly 700 people for an exploration of Indigenous futures. Vanessa Scott provided this account of the proceedings.

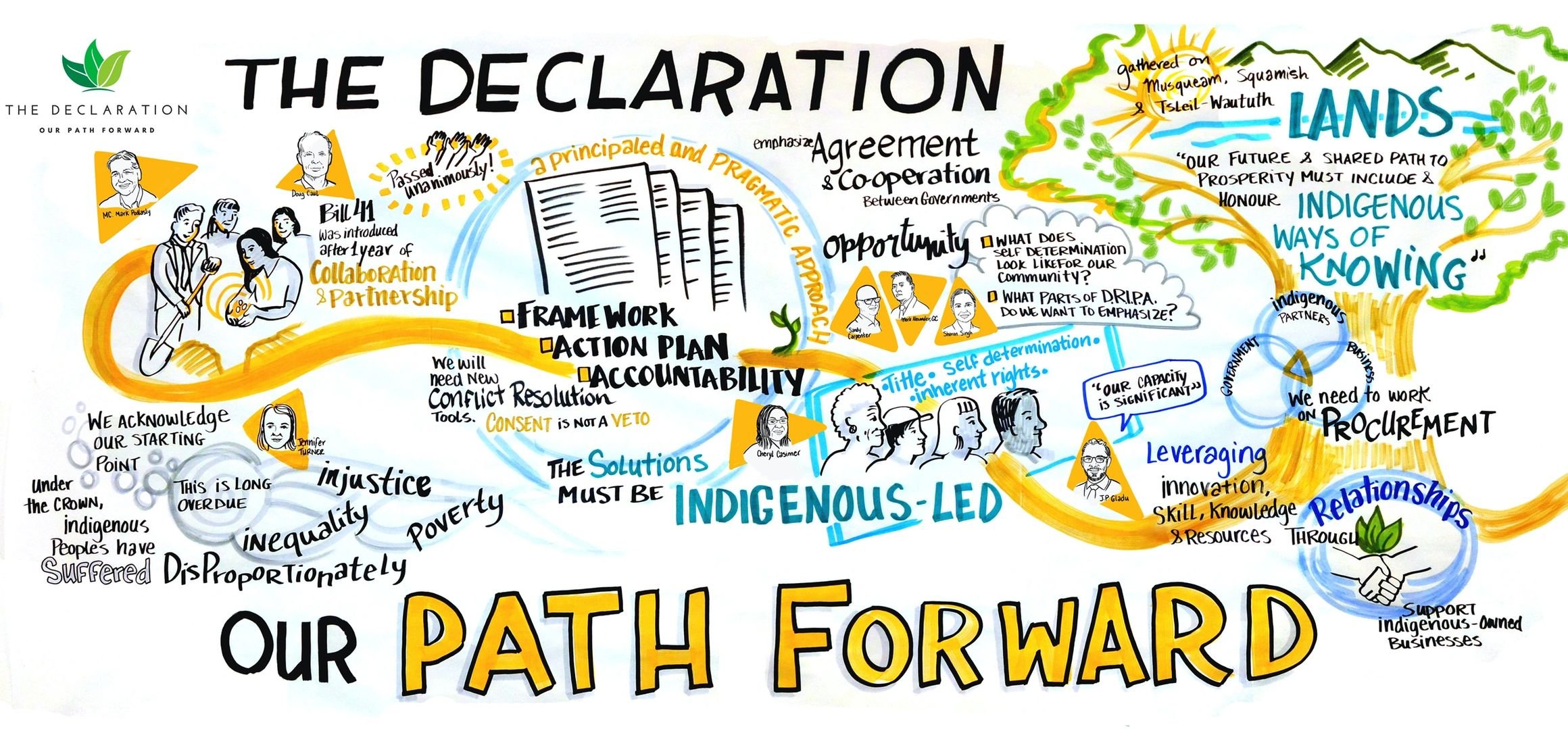

On January 14, 2020, The Declaration: Finding the Path convened a historic event on Indigenous rights and our shared future. For the first time in Canadian history, British Columbia has become the first jurisdiction to pass legislation that commits our government to align its laws and public policies with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). Translating this vision into action – and collectively forging real steps to implementation – is the task and necessity of the times.

By harnessing this spirit of collaborative leadership, Finding the Path delivered BC’s first all-day special event highlighting Indigenous voices and perspectives on the implementation of UNDRIP.

Embodying the transparency, openness and trailblazing required, our innovative format enabled us to explore: What are the implications and examples of obtaining ‘Free, Prior and Informed Consent’? What do steps to success in business partnerships look like and how do you get there? What do we do when consent is not obtained by negotiation? And what do elected and Hereditary leaders from diverse Indigenous communities think about the future of shared decision-making?

On the traditional territories of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations, we gathered the collective wisdom of over 45 speakers and more than 550 participants to clarify the path forward. Using an innovative audience feedback platform enabled panellists to answer real-time questions about the foremost issues and concerns on people’s minds. This included direct statements on the Coastal GasLink pipeline that may be even more relevant in retrospect. In the weeks since this gathering at the Vancouver Convention Centre, the significance of these insights has increased in value.

The Declaration’s full day of speakers, dialogues and music showcased success stories and challenges from which we can all learn. During an era of transformation for Indigenous rights in BC, Canada and internationally, we were reminded throughout the day of the many ways in which we can show leadership as “The world watches us.”

Each speaker shared their personal expertise and community experiences working to secure the future of Indigenous rights implementation and an equal footing in economic development.

The following summaries showcase some of these key takeaway statements, including words of caution, agreement and optimism. By making these insights more widely available, we can better navigate the path ahead as British Columbia's change-making legislation incorporates 46 UNDRIP principles into provincial law and policy. How the legislation is translated into benefits and change on-the-ground in our communities is a Call to Action for all of us to take part.

Traditional welcome.

“Welcome to a new era led by vibrant, forward-thinking Indigenous cultures."

— Dennis Thomas, Tsleil-Waututh Nation

Opening remarks.

Jennifer Turner, 2020 event director.

In her opening remarks, Finding the Path Event Director Jennifer Turner set the context for this historic opportunity to build healthier, more constructive relationships.

“No more box-ticking or tokens,” she said, “Words alone won’t lead to a new path.” One key insight is that “Economic security is part of prosperity but includes much more.”

She concluded: “We will be stronger for the journey only if we take the right path together.”

A youth message.

Twelve-year-old Bella Stark-Jones of Tsawassen First Nation welcomed participants by singing the Women’s Warrior Song.

Cheryl Casimer (First Nations Summit Political Executive) said this “Grounded us and helps us start in a good way,” because Bella embodies the positive historic changes underway as a youth leader.

Master of Ceremonies Mark Podlasly (Economic Lead to the First Nations Major Projects Coalition) agreed and told the audience: “Remember Bella, remember her face, her spirit and her song – it is why government has taken this step to make sure UNDRIP comes into force in BC.”

Cheryl Casimer.

Cheryl Casimer pulled back the curtain on key emerging details of Indigenous Rights in Canada and used her first-hand knowledge to recommend the most useful background reading for the audience. Topmost in her suggestions were the Principles that Guide the Province of BC’s Relationship with Indigenous Peoples, which comes out of work by former Minister Judy Wilson-Raybould and the federal government in 2017. Also see BC’s Joint Agenda: Implementing the Commitment Document for ideas on the Agenda, Vision and Roadmap to the systemic shift underway in our province.

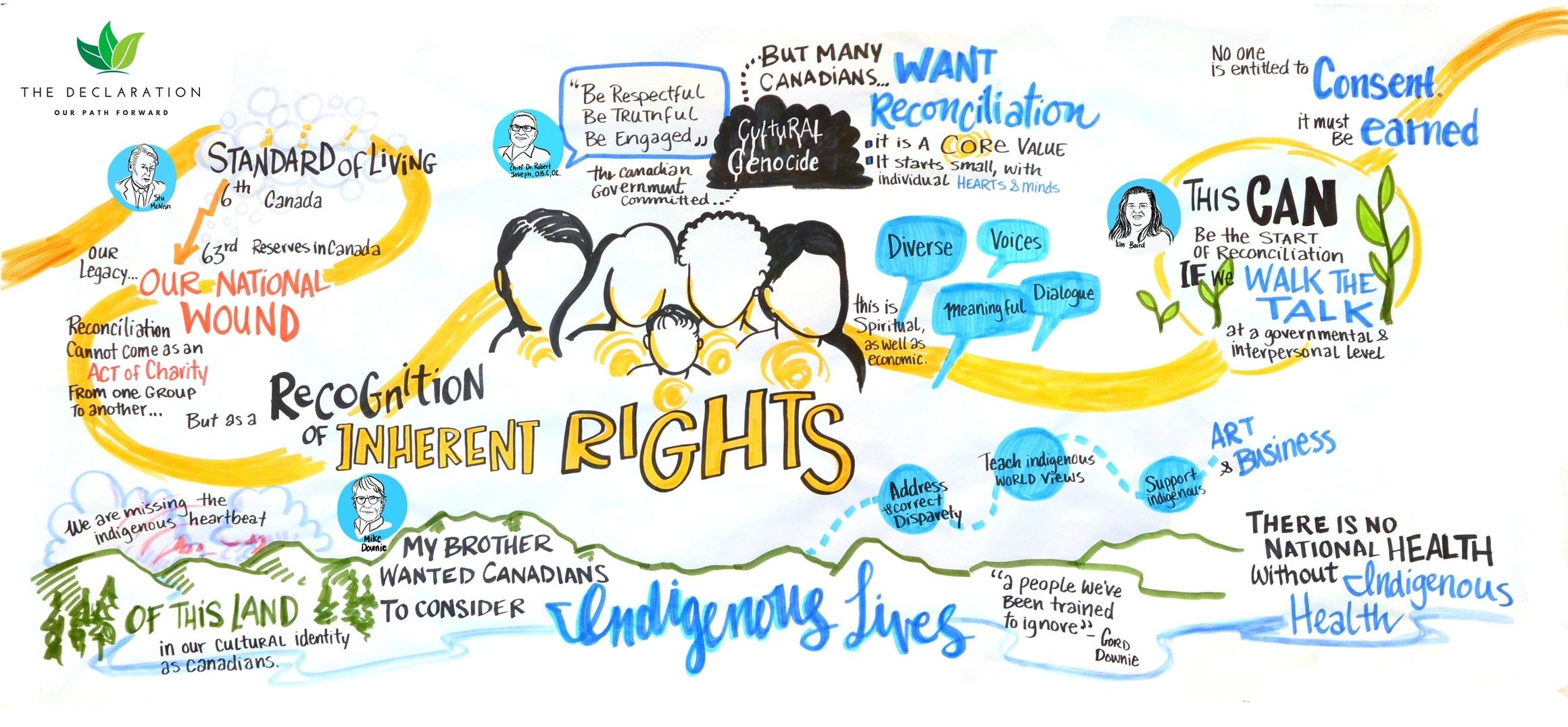

First Nations have been “Waiting to have this discussion for too long,” said Cheryl, underscoring that this transformation “must be led by Indigenous Peoples and Indigenous Nations.” This is about “Basic human rights, ensuring health and prosperity and ensuring First Nations are part of the political, economic, social and cultural fabric.”

JP Gladu.

JP Gladu, then CEO of the Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business, drove home the message that this “Is about putting in place structures to manage wealth, not structures to manage poverty, which is a significant departure from the last 150 years.”

Across Canada, he said, communities are split and polarized but “The majority of Canadians see the economy as a means to achieve reconciliation.”

Stating that First Nations “Are no longer on the outside of the economy but leading it,” he explained: “We are Canada’s First Entrepreneurs and we’re learning to flex our muscles in a modern context.” But in order for this to happen successfully he cautioned: “Reliable data needs to precede policy change.”

Legal perspective: three voices.

Applying UNDRIP: What does UNDRIP mean for companies and Indigenous partners?

The Legal Panel explored the potential of this new legislation to provide greater respect for First Nations and increased certainty for investors in BC. Sandy Carpenter, Canadian Regulatory and Indigenous Law, explained that UNDRIP is compatible with the Canadian Constitution and is not any major departure from existing law – so what then is the most powerful part of the legislation? The section that directs the overarching alignment with all of BC government laws and public policies.

“If the legislation achieves reduced poverty and increased prosperity, it will be a success and a sea change within this province,” said Sandy. But “It is a hollow opportunity without political action. To be serious about reconciliation, First Nations must decide for themselves what they want to capitalize on.”

Sharon Singh of Bennett Jones, who consulted on behalf of the mining sector on Bill 41 at the invitation of the BC government, summarized that DRIPA legislation “Broadens the interpretation of rights and informs changes to the provincial judiciary.”

As a voice of caution, Merle Alexander, an Indigenous lawyer and hereditary Chief who helped to draft Bill 41, stated that there are “Dangers too where industry and the Crown could make a conscious effort to narrow the interpretation of the Act” unless we “Call into question complacency with the status quo.”

DRIPA requires the development of an Action Plan to achieve legal harmony between BC government laws and the UN Declaration. See the BC government’s DRIPA FAQs.

“Remember UNDRIP is not an economic or resource treaty – it’s an international human rights treaty,” Merle stated to the non-Indigenous business and legal representatives. “You have to realize it’s not about you. It’s about government-to-government relations.” But, he said, “It does have huge impacts on everyone’s day-to-day lives and businesses.”

When asked what to do if consent is not achieved by negotiation, Merle said we need greater expertise to address rights-related disputes. Indigenous communities “Must be the ones to decide how and who should lead their governance structures along a spectrum” from Hereditary to Indian Act leaders. To achieve this we need to “Prioritize alternative dispute resolution mechanisms outside of the courts,” said Merle. “First Nations communities not lawyers” should be the decision-makers going forward. The legal panelists agreed that consent is about both the ability to Say Yes and Say No but the Canadian government still must make its decisions in the public interest.

A message of hope.

Chief Dr. Robert Joseph is a national hero and a peace-builder whose life and work are examples of his personal commitment to justice. A Hereditary Chief of the Gwawaenuk First Nation, Chief Joseph has dedicated his life to bridging the differences brought about by intolerance and racism both at home and abroad. He addressed “The spirit of our future – because I have never before seen so much attention on our shared history and how to move forward together.” He advised UNDRIP can be “An instrument of inspiration for us all” and an important measure: “How deep is our humanity? How high are our intentions to work together? Now we can sow seeds for many generations.”

Speaking to the heart of the matter, Chief Joseph advised: “What you need to understand about CGL (Coastal GasLink pipeline) and the Wet’suwet’en, what brings us here is that they are defending what for millennia is part of them. It’s a signal to the rest of us that there are considerations beyond the narrow outlook…It tells us we need to do more work and find new ways of confronting old problems. Please stay the course.”

Chief Joseph asked the audience to commit to the idea that “We can all join hands and create a better life for all of society and all of our children…. Do everything you can to increase the quality of life for all of us. Keep the momentum going!” To achieve this he stated with conviction that we must make reconciliation a core value:

“Our ancestors always knew reconciliation is a journey, a life way, that’s why it is a core value.” With the powerful statement that reconciliation is an ancient spiritual imperative of all people, he concluded: “If we are to enact reconciliation in this country, it must have a spiritual component. That will be the glue that holds reconciliation together.

“Residential Schools made me a broken human being and that is not the kind of society we want to create, one that perpetuates brokenness. We must transform our country together into a vibrant country where all can achieve fullest potential.” Chief Joseph acknowledged that “We are currently witnessing many harmful divides in society. We’ve heard the words before but now we must put them into practice. Know that we all belong, we all have a right to be here, we all have responsibilities and we all want to cherish the future and our children.”

A special report on the future of the Salish Sea.

Salish Sea panel, left to right:

Chief Harley Chappell of Semiahmoo First Nation; Tsawwassen First Nation chief administrative officer Braden Smith; and Councillor Deborah Baker of Squamish First Nation.

Drawing Change.

Corporate Canada called to action.

The following is from the 2016 Truth & Reconciliation Commission on Indian Residential Schools chaired by the Honourable Murray Sinclair.

We call upon the corporate sector in Canada to adopt the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as a reconciliation framework and to apply its principles, norms, and standards to corporate policy and core operational activities involving Indigenous peoples and their lands and resources. This would include, but not be limited to, the following:

Commit to meaningful consultation, building respectful relationships, and obtaining the free, prior, and informed consent of Indigenous peoples before proceeding with economic development projects.

Ensure that Aboriginal peoples have equitable access to jobs, training, and education opportunities in the corporate sector, and that Aboriginal communities gain long-term sustainable benefits from economic development projects.

Provide education for management and staff on the history of Aboriginal peoples, including the history and legacy of residential schools, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Treaties and Aboriginal rights, Indigenous law, and Aboriginal–Crown relations. This will require skills based training in intercultural competency, conflict resolution, human rights, and anti-racism.

Contact us.

For media, sponsorship or other questions: inquiries@indigenoussuccess.ca